BY RITA BOOK* In the hands of Chris Ware, the funnies aren’t particularly funny. Unless, that is, lonely misfits and their existential lives of quiet desperation is your idea of comedy gold. Ware’s deeply felt, darkly told and beautifully illustrated stories, including the partly autobiographical “Jimmy Corrigan” and “Rusty Brown,” have won awards in the U.S. and abroad, drawn comparisons to “Ulysses” and Duchamp, and landed the Chicago-based cartoonist on bookshelves, museums and galleries, The New York Times, The New Yorker and Esquire. Ware’s latest, the groundbreaking and gorgeous “Building Stories,” has already been called his magnum opus and a new high-water mark for the graphic novel as an art form.

BY RITA BOOK* In the hands of Chris Ware, the funnies aren’t particularly funny. Unless, that is, lonely misfits and their existential lives of quiet desperation is your idea of comedy gold. Ware’s deeply felt, darkly told and beautifully illustrated stories, including the partly autobiographical “Jimmy Corrigan” and “Rusty Brown,” have won awards in the U.S. and abroad, drawn comparisons to “Ulysses” and Duchamp, and landed the Chicago-based cartoonist on bookshelves, museums and galleries, The New York Times, The New Yorker and Esquire. Ware’s latest, the groundbreaking and gorgeous “Building Stories,” has already been called his magnum opus and a new high-water mark for the graphic novel as an art form.

PHAWKER: You’ve said you weren’t a big reader of comics as a kid, but that one you cite as an influence is ‘Gasoline Alley.’ What made it so compelling to you? It’s easy to see the visual influence but was there anything specific  about the narrative that was influential also?

about the narrative that was influential also?

CHRIS WARE: Actually, I read a lot of “Peanuts” and collected superhero comics, the latter because I thought they were a true window into the adult world and I traced the pictures of the muscular men in some hope that it might impart, I guess magically, some sort of more maturity to my scrawny frame. I only started reading “Gasoline Alley” in college because Frank King, the cartoonist of the strip, was able to communicate gentleness and warmth using the staccato tools of comics. As well, the theme of the strip (that of a man raising an orphaned boy) appealed to me.

PHAWKER: In its glowing review of “Building Stories,” The Guardian says: “When you read a Chris Ware comic you can be fairly sure that you’ll end up with a migraine from the tiny writing, or suicidal from the worldview, and yet he’s so damn good you do it anyway.” Assuming your goal isn’t making your readers migrained and suicidal, what is it that you’d like people to get out of this work, or any of your work for that matter?

CHRIS WARE: I have absolutely no idea. You’re indeed correct, however, that I don’t want to induce headaches or suicide (I think the Guardian reviewer was simply trying to be funny.) If anything, my attempts to try and reproduce something of what I think of as the complicated textures and feelings of life on the page may end up looking a bit daunting, though I don’t intend them to be. Mostly, I don’t want the reader to fell gypped, or that I haven’t made a real effort on his or her behalf.

PHAWKER: Not having seen “Building Stories,” the description — a box with 14 different books, pamphlets, posters and other items that put together in any order create a complex narrative about a Chicago apartment house and its people — makes it sound like it must have been a huge undertaking to execute. How long have you been working on all the pieces of the puzzle? And why make it a puzzle at all? What does this do that a straight-up bound book can’t?

CHRIS WARE: I’ve been working on “Building Stories” off and on for the past 11 years while working on another graphic novel (currently at 250 pages) and other projects. The book itself is an attempt to create another physical means of seeing around and into memories in print in something of the way that I think our minds allow us to already; it’s not a puzzle at all, but hopefully has something of the appeal or promise of one. It’s about how life changes once one decides to have a family and children, how the current sort of reverses itself from an inward to an outward direction.

CHRIS WARE: I’ve been working on “Building Stories” off and on for the past 11 years while working on another graphic novel (currently at 250 pages) and other projects. The book itself is an attempt to create another physical means of seeing around and into memories in print in something of the way that I think our minds allow us to already; it’s not a puzzle at all, but hopefully has something of the appeal or promise of one. It’s about how life changes once one decides to have a family and children, how the current sort of reverses itself from an inward to an outward direction.

PHAWKER: In 2001, CityPaper here in Philly became the third alt-weekly in the country (after Seattle’s The Stranger and Chicago’s New City) to carry “Rusty Brown” in full-page four-color weekly installments — and reaction was swift and negative. Over several weeks’ worth of letters to the editor, the most repeated phrase was “relentlessly depressing,” as well as far less kind descriptions. You actually told CP’s editors before “Rusty” even ran that readers would be “puzzled and angry.” Why did you think that? Have you experienced that kind of visceral reaction before, or since, with other characters? Or is there something about Rusty, the sad bullied kid who grows into a sad pathetic adult, that strikes a nerve?

CHRIS WARE: If I remember correctly, I was worried that beginning the story in the middle, as I believe I did, would leave many readers confused and baffled as to what was going on. I knew that I was serializing a story with weekly breaks that weren’t exactly reader-friendly, but that these breaks were unavoidable given the structure that the story had already taken. As well, warning the editors in this way was sort of an apologetic, pre-emptive strike against my regular fears of being disliked, which I suppose is something of a midwestern cartoonist problem, if not just a personal one.

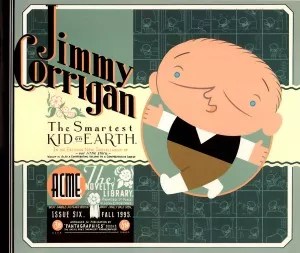

PHAWKER: Before Rusty there was “Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth,” probably how many readers first became familiar with your work (thanks in part to Art Spiegelman who brought you on at RAW in 1987). You’ve mentioned that the Brit-talking baby Stewie from “Family Guy” bears striking similarities to Jimmy — coincidence or not?

CHRIS WARE: I have no idea whether it’s a coincidence, though Stewie’s design does bear a certain passing similarity, at least to my eye. I was recently very impressed after I read the New Yorker profile of Seth McFarland, however, as he seems to work extremely hard; I didn’t realize he was still so involved in every aspect of his show. That’s an incredible amount of work and pressure.

PHAWKER: Are rumors true or false that you’re trying to disappear “Floyd Farland, Citizen Of The Future” from your late ’80s UT-Austin days by buying every copy you can find and destroying them all? If true, why? Is it really THAT bad?

CHRIS WARE: Yes, it really is that bad.

PHAWKER: Talk about the Fortune magazine cover you submitted in 2010 for the “Fortune 500” issue. As rich guys dance on top of a looming ‘500’ skyscraper, the American landscape below is home to a 401(k) cemetery, underwater houses in the Gulf, Big Box Super Glut retail, Stocks & Bonds Casino and Toxic Acres suburban development. Did you send it knowing it’d be rejected but wanting to make a statement to the editors, or did you think there was a chance, however small, that they’d love it?

CHRIS WARE: The art director very kindly invited me to do the cover and I tried to approach it as objectively as possible — or at least as objectively as doing a cartooned sum-uppance of the state of the financial world was possible — and I realized about halfway through it that it was highly unlikely it would see print. Still, I sent it in with a note to that effect, since Fortune was known in its early years as a progressive magazine. My first hunch was right, however, though I didn’t expect it to metastasize like it did. I wrote an apology to the art director, whom I’ve for years, as it was certainly not my intent to stir anything up. Then again, the TARP act and the Dodd-Frank Act were created in reaction to >something< that went wrong, right?

PHAWKER: You have published graphic novels, newspaper cartoons and New Yorker covers. You’ve also shown at the 2002 Whitney Biennial (as the first comics artist ever chosen), the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and the Sheldon Museum in Nebraska. Do you consider yourself more a cartoonist, a graphic novelist, an artist? Are they one in the same?

PHAWKER: You have published graphic novels, newspaper cartoons and New Yorker covers. You’ve also shown at the 2002 Whitney Biennial (as the first comics artist ever chosen), the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and the Sheldon Museum in Nebraska. Do you consider yourself more a cartoonist, a graphic novelist, an artist? Are they one in the same?

CHRIS WARE: I prefer the word “cartoonist” because it seems to be the least pretentious. The last thing I’d want to telegraph by my chosen vocation was that I was trying to pull something over on someone, which seemed to me to be occasionally the case with some of the artists I learned about when I was in art school (though not all, by any means.) Mostly, I’ve found that as a cartoonist the reader lays no blame at his or her own feet if a cartoon makes no sense; one blames the cartoonist, which I think is a much clearer relationship between reader and writer, or viewer and artist, than that of the fine art world, depending on how one wants to look at it.

PHAWKER: You have a young daughter now. Has being a father changed your work? Any plans for some lighthearted fare about some not-even-a-tiny-bit-sad babies and their unpredictably adorable ways?

CHRIS WARE: It’s a fair amount of what makes up “Building Stories,” actually, or at least I hope that it does.

*(aka JOANN LOVIGLIO)

[Click HERE To Enlarge]