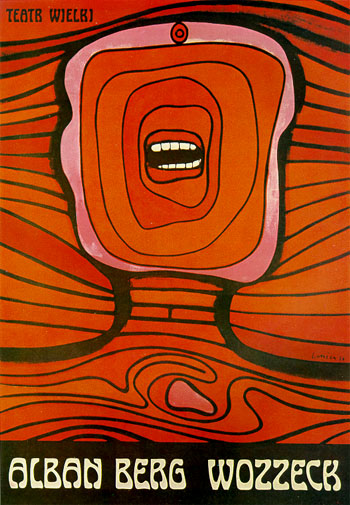

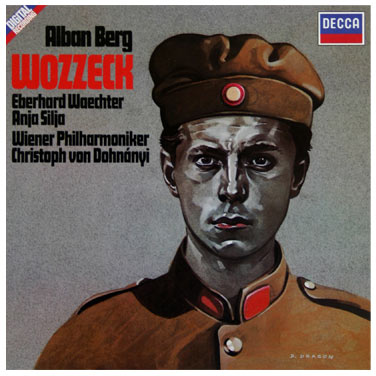

BY DAVE ALLEN Opera might be stereotyped as stuffy and uninteresting, but sex, violence and mayhem have always been part of the medium. Alban Berg’s 1925 opera Wozzeck takes these traditional elements and frames them, to startling effect, in a score of dissonant but sensual and compelling music. It’s a work that has never fallen easy on the ears of American audiences, but this weekend, Philly’s famed but deeply traditional Curtis Institute of Music, in a co-production with the Opera Company of Philadelphia and Kimmel Center Presents, is putting on this revolutionary work of early 20th-century modernism and, as a friend who’s a Curtis grad put it, “stepping out of the 19th century.” Two of Curtis’ fastest-rising alumni appear in lead roles, including Jason Collins, a 2003 master’s grad from Curtis, who plays the vain, sadistic and supremely arrogant Drum Major. It’s a big leap for Collins, a friendly, modest South Carolina native who’s on the verge of making a huge splash in the opera world, and he talked with me about getting into character as a complete bastard, his alma mater engaging in some innovation, and the future of opera. Hint: it has nothing to do with monocles or evening gowns.

BY DAVE ALLEN Opera might be stereotyped as stuffy and uninteresting, but sex, violence and mayhem have always been part of the medium. Alban Berg’s 1925 opera Wozzeck takes these traditional elements and frames them, to startling effect, in a score of dissonant but sensual and compelling music. It’s a work that has never fallen easy on the ears of American audiences, but this weekend, Philly’s famed but deeply traditional Curtis Institute of Music, in a co-production with the Opera Company of Philadelphia and Kimmel Center Presents, is putting on this revolutionary work of early 20th-century modernism and, as a friend who’s a Curtis grad put it, “stepping out of the 19th century.” Two of Curtis’ fastest-rising alumni appear in lead roles, including Jason Collins, a 2003 master’s grad from Curtis, who plays the vain, sadistic and supremely arrogant Drum Major. It’s a big leap for Collins, a friendly, modest South Carolina native who’s on the verge of making a huge splash in the opera world, and he talked with me about getting into character as a complete bastard, his alma mater engaging in some innovation, and the future of opera. Hint: it has nothing to do with monocles or evening gowns.

***

***

PHAWKER: So my understanding of the role is: you’re a jerk. You seduce a man’s wife, you brag about it in front of him and his friends, and then you beat him up. So how are you rehearsing for being a jerk — are you walking around kicking puppies?

JASON COLLINS: It’s fun. It’s an adventure. I hope I’m not that kind of person on the outside. I try not to be, anyway. There’s just a level of confidence that one has to have. Y’know, if you’re going to be a bad-ass, you’re going to be that guy. He’s just that guy. You just have to step in. The way his music is written, it’s kind of balls-out… I don’t know how you can write this, but… dick-swingin’ music. It’s just kind of there. He thinks the world of himself and kind of lets everybody revolve around him. If it was ‘The Drum Major,’ it would just be about this man… It takes me a lot of focus to get into there and it takes me a lot of abandon. Like, I have to walk in and just abandon self and abandon that I’m not that kind of person, but he is, and to honorBuchner and honor Berg, I have to kind of abandon Jason Collins and kind of let this man go. Berg did a great job. His music is just right there; it’s militaristic, it’s bombastic, and it’s sexual. And when he beats Wozzeck up, it’s in the barracks when he’s trying to sleep where he’s just been in this tavern scene, and Emma Griffin is just genius, she’s painted this great picture of him going crazy  watching his wife get molested. He takes her off and crosses in front of him — boom — and then the next scene I come back without my shirt, or just in a t-shirt, obviously having just had sex with his wife, and I beat him up while he’s trying to sleep. I don’t beat him up in the bar. I humiliate him, and her, too. She just thinks how he’s honored by the prince, I’m excused of all military duty. If they’d set it in this Nazi-era time, he could definitely be the figurehead of the Aryan race. He could be that guy. He’s what the prince keeps saying Ich bin ein Mann — “I am the man.” So he’s been delivered this message from the highest-ranking person, so one tends to believe that. I often feel a little self-conscious after I’m finished because I’m like, “God, did I just let go like that?”

watching his wife get molested. He takes her off and crosses in front of him — boom — and then the next scene I come back without my shirt, or just in a t-shirt, obviously having just had sex with his wife, and I beat him up while he’s trying to sleep. I don’t beat him up in the bar. I humiliate him, and her, too. She just thinks how he’s honored by the prince, I’m excused of all military duty. If they’d set it in this Nazi-era time, he could definitely be the figurehead of the Aryan race. He could be that guy. He’s what the prince keeps saying Ich bin ein Mann — “I am the man.” So he’s been delivered this message from the highest-ranking person, so one tends to believe that. I often feel a little self-conscious after I’m finished because I’m like, “God, did I just let go like that?”

PHAWKER: The work is really dark and filled with soul-crushing oppression and militarism. Does it get to you? Or is it your job as an actor to rise above that?

JC: It’s our jobs as actors to leave it in the room, but it’s very difficult. I talk with the Maestro [conductor Corrado Rovaris] about it, and I have to go home and sing some Mozart or some Verdi, just technically, in terms of vocal approach. It’s so angular and so angry, and it’s so dark. It’s all over. So I have to get back to some roots on that, and emotionally, it’s not so bad on the Drum Major. I feel a little guilt-ridden sometimes because he’s such a jerk, but you have to learn how to separate that. You have to be able to walk off and (whistles, wipes a hand over his face). My agent used to — when JonVickers was singing, she was his agent too — sit in the wings for the final scene of Peter Grimes, and he would just walk off and be like, “Come on, let’s go get a hamburger.” And he was able to leave it on the stage. It’s a great outlet of emotion when you can tap into that and it’s a great luxury to be able to be a jerk on the stage, and no one will hate you for it. You can leave it there. Wozzeck is a different story, but Shuler is such a fantastic actor, I’m sure he’s mastered his craft enough that he can leave that behind as well. But it is our responsibility, but we all are just fried. Last night, we had a run, it was just (forceful exhale). You don’t even know what to say, because you can’t give notes. You said, “We’ll do notes tomorrow.” You just have to have a break, and I usually watch some kind of mindless TV or something to get my mind off of it. It’s just dark and just depressing.

PHAWKER: You played this role six years ago for the Opera Festival of New Jersey. What do you feel you’ve learned in the last six years about the role and yourself that you want to bring to these performances?

JC: Well, I would say, if I’m personally speaking, how to leave it in the theater. Thank God I had Curtis here, because I was trained to do that. Mikael [Eliasen, director of vocal studies] challenged me to do big scenes and picked things that would make me do that. Now, I think there’s more assurance. I’ve been working, I’m a working singer and a singing actor. I’m comfortable in myself and in my work ethic and my preparation levels now, and my vocal abilities, and so when I was just finishing being a student — well, I’ll always be a student, but I had literally just graduated — and I was still working things out, so I couldn’t exude the confidence that the Drum Major has to exude. He has to just walk on and everybody just (he freezes). They have to think, “Is he going to kick me? Oh thank God, he just beat Wozzeck up tonight. He didn’t beat me up tonight.” I think that’s what I’m bringing differently this time is just a confidence in Jason, and so Jason can let go and let the Drum Major be arrogant.

JC: Well, I would say, if I’m personally speaking, how to leave it in the theater. Thank God I had Curtis here, because I was trained to do that. Mikael [Eliasen, director of vocal studies] challenged me to do big scenes and picked things that would make me do that. Now, I think there’s more assurance. I’ve been working, I’m a working singer and a singing actor. I’m comfortable in myself and in my work ethic and my preparation levels now, and my vocal abilities, and so when I was just finishing being a student — well, I’ll always be a student, but I had literally just graduated — and I was still working things out, so I couldn’t exude the confidence that the Drum Major has to exude. He has to just walk on and everybody just (he freezes). They have to think, “Is he going to kick me? Oh thank God, he just beat Wozzeck up tonight. He didn’t beat me up tonight.” I think that’s what I’m bringing differently this time is just a confidence in Jason, and so Jason can let go and let the Drum Major be arrogant.

PHAWKER: Since then, I know you’ve done some Wagner. What are your thoughts on some of the controversies surrounding him, his philosophies and his music?

JC: I grew up with Pavarotti, so I just knew of Italian singing, but Wagner is, to me, the Shakespeare of opera as a whole entire art form. You’ve got Mozart, who’s musically a genius, and da Ponte, who’s a wonderful, ingenious librettist. You have Verdi, who’s a master of vocal writing. But if you want a complete opera, to me, Wagner just does it. His libretto, his word choices, his alliterations — nothing’s just “oh, okay, that’ll be fine.” I started Juilliard a couple of years later, so I was 20 and everybody else was 18, and I remember getting in such a heated debate in music history class. They played something from Wagner, “Ride of the Valkyrie” or something that everyone would know, and I wasn’t a great student and was not well-educated in music at that time. It was my first year. And they’re like, “Listen to how nationalistic this music is.” (He sings the famous melody from “Ride of the Valkyrie.”) I said, “That just sounds like great music to me. It doesn’t sound nationalistic to me.” They’re like, “How can you dare say it’s not nationalistic?” “Because I’m hearing it for the first time, and I don’t know anything. I’m just hearing it as music for the first time.”

Wagner can’t help who chose his music to march his troops to. We have “Yankee Doodle Dandy” or whatever we want to march our troops to. Whatever motivates people is beyond a dead man’s choice, I would say. I don’t know, I try to avoid that because, for me, the music is first, and it’s beautiful music, and it can be delivered in a way that that beauty comes across, not anything else. There are so many musical geniuses that, because of their genius, their faults get overlooked. Because their music is just greater than any fault that they could have. I think Wagner goes beyond that. I think the beauty of his music and his texts and everything are what they are, and I hope that, given the progressive nature of our country and where we are, that… it wasn’t that long ago that black people couldn’t even ride a bus. Now we have Barack Obama as our president, and that’s wonderful and exhilarating to me. If that shows anything, it shows that people can accept the beauty of what Barack Obama is, and I hope that’s a sign of the possibilities.

I mean, “Der Rosenkavalier” is one of the most beautiful things ever, and I don’t particularly care what Strauss’ personal views were on the Jewish race, nor do I really care what Wagner’s were. I only care about Wagner’s music. And it’s my responsibility and a privilege to get to deliver it in a beautiful and meaningful way with zero hatred, with just love. I think that’s the glory that he left behind. Here, he’s allowed his personal views, you’re allowed your personal views, and I’m allowed mine. And that’s what being an individual is all about, but he wrote music for the world to share, and I think that’s what we do: Make music. He’s given us this great gift. Nothing in “Der Valkyrie” says anything about his personal feelings toward any particular race. It just says, “Here’s some of the most gorgeous music in the world. Here’s the greatest libretto in the world. Here, go make it yours.” And that’s my privilege. That’s a real honor to be able to do that.

PHAWKER: Wozzeck is a tad more daring or adventurous than what Curtis usually does. Having studied here, did you think they would do something this modern?

JC: Oh, I’m not surprised. Mikael’s had a fascination with Wozzeck for a long time. You just can’t cast a Drum Major from a student. You could, but it wouldn’t be beneficial. It wouldn’t be a learning process. It would be, let me cross our fingers. It’s just hard. Same thing with Wozzeck. But with the Doctor and the Captain and everybody down to the chorus, it’s very hard. But as you know, these are extraordinary singers and musicians, extraordinary talents. Together with the Opera Company of Philadelphia, merging this together in the Kimmel Center, it was a great realization, and Mikael went to long lengths to get alumni that were capable of doing this. It’s the first time in history they’ve ever brought in alumni to sing in an opera here. The first time this was done, as an American premiere, was also a co-production with the Opera Company of Philadelphia and Curtis. They were both involved in it together, and now we’re bringing it back. But it doesn’t surprise me, because if Mikael could find a way to do it, he will. Same thing as when I was here — we had the voices to do Vanessa, and we did it. That’s what Mikael does. It’s not just a business. There are conservatories that are turning into businesses, but I feel that he remains true to the talent he has. The kids — I shouldn’t even call them kids — my colleagues are coming up. He sets the bar and makes them come up to it. It’s professional level, and they’re great. I hope it pushes on to braver and bolder things.

PHAWKER: What’s been your experience with Philly audiences?

JC: I love Philly audiences. I always have a great time performing in Philadelphia. It’s close enough to the New York scene, but it’s not a scene. It’s a real music-lovers town, I find. It’s not a “my diamond’s bigger than your diamond, let me show you, I’m at the Met opening.” It’s like, “Ooh, I’m going to see Wozzeck, I hope I can get tickets.” It’s that kind of crowd. It’s a musicians’ haven. I find I make really good music here, and I don’t know if it’s because I was educated here. I’m kind of vagabond in my career, but I feel grounded here. I feel like I can trust the audience, I can trust the presenters. And the audiences, I find that they’re very appreciative of honest music-making.

PHAWKER: Where do you see the future of opera heading? Obviously there’s been a rise in these movie theater broadcasts. Are you worried about how you’ll look in HD?

JC: I think that’s the wonderful thing and, y’know, I was 75 pounds heavier a year and a half ago. So it’s definitely heading in a direction where you have to look the parts. It’s no longer the fat lady singing anymore. It’s becoming more theatrical. A great teacher of mine, Richard Bado — I don’t think he’ll mind me quoting him — once said, “Musical theater is theater enhanced by music, and opera is music enhanced by theater.” It was a wonderful quote. Basically, I hope in opera that the emphasis stays on good music-making, and then the emphasis on the theater. I mean, they’re very close, but overall, I’d rather hear a great Traviata than see someone rail-thin who can’t sing it, because there’s a responsibility to your material.

I love the HD broadcasts. It’s bringing in new audience and bringing in a lot more interest. These theaters are selling out for these broadcasts, and that’s great. There are these great people — the Flemings, the Mattilas, Deborah Voigt, Jonas Kaufmann — these people, they’re embodying everything now, and I think it’ll become a great art form like that because they are embodying great singing and great looks. There can be extremes, I mean. Pavarotti, he just had to stand there, but his voice was enough. There wasn’t a better voice. So he could do whatever — just stand there and be propped up on the stage. He was in his own league, way different than anyone else.

The economy worries me, with this art form, but I think it’s steadying off, and I think people are realizing that they’re responsible for all aspects. You’re responsible for your music, you’re responsible for how you look, you’re responsible for your acting skills. It’s not just one part. It’s not a concert, it’s not a play. It’s opera. And so I’m glad that there’s been some emphasis on it, because I want to see it. I want to see and hear a great Traviata at the same time. That’s going to keep me on the edge of my seat. That’s going to make people want to come back. That’s going to get people excited when they see that on the screen, whether they’re seeing it in HD or seeing it live. That’s the essence. That’s what people want from the art form. That’s what the composers, I think, had in mind — Wagner, Verdi, Puccini. I’m sure they didn’t write Mimi for some 300-pound bear of a woman, or Rodolfo, the starving artist, for that either. I’m sure in their visions, in their head, they said, “This is what it looks like.” When they were sitting across the table, when it was modern music, I’m sure they had a concept. But then there are voices that supersede all that, and there are actors and actresses who supersede all that. I think it’s leveling off. I think it went a little (whistles, makes a veering motion with his hands) just at the onset of the theater being broadcast and the commercialization of opera, but it needed that. It needed a stirring, I guess. Once it stirs and sits, it becomes something real. I think it’s getting there.

PHAWKER: In this production, you’re working with Shuler Hensley. He’s a large man, bigger than you, and you have to boss him around and beat him up. How are you going to handle that?

JC: He is an incredible singing actor, and we don’t… we were talking the other day, and I was thinking, how does one become homeless? I see these people in New York… at what point are they homeless? At what point does everything abandon them and they seem so weak? Even these huge people who are homeless. And when the curtain opens up on Wozzeck, he’s kind of at the bottom. He’s biting the hangnails off of someone and shining their shoes, and there’s a vulnerability and a weakness that comes into seeing somebody do that. And I beat him when he’s down. Had he had a privilege as a man that he would rise up, but he didn’t. The character of Wozzeck didn’t have that privilege, to be born into that, therefore I attack him where he’s most vulnerable: his wife, and when he’s sleeping, when he feels the most secure. He has given up on himself, I feel, and he’s just trying to do whatever he can — shine shoes, go into a back alley for an experiment with a doctor — just to get some money. The only shred of dignity, and it’s a very small thread, is that he loves Marie, and he believes she loves him, and he has to provide for this kid. He’s not getting a government check every month, and so he doesn’t care, and it makes it easy to beat up on someone who doesn’t care about themselves. What’s the saying… “As a lion, you only have to be as fast as the slowest gazelle.” And I think that’s what the Drum Major is. He’s not going to go up to someone on his level, and there’s higher ranking people. There’s the Captain, who’s higher-ranking than the Drum Major. I’m just leading the corps in parades. Shuler gives that vulnerability of — “Oh yeah, are you going to give me a drink? I believe you” and then POP! He’s down, and he doesn’t feel like he’s worth it. He really delivers that on the stage, and you feel bad for him. As big as he is, in physical form, he makes Wozzeck tiny. He makes it very easy to beat him up, when I know afterwards that, if we were out having a drink, he could take me out in a second.